On the early Wednesday morning of October 5th, 1898 a handful of young Pillager men held off approximately 100 U.S. soldiers on the shores of Sugar Point. The firefight resulted in seven dead and ten wounded with no casualties reported on the Ojibwe side. The soldiers were eventually forced to retreat back to Walker, MN. This event has come to be recognized as the last military conflict between the U.S. and American Indians.

As with many conflicts, the tensions that led to the Battle of Sugar Point were varied. Lumber companies routinely swindled the Ojibwe people out of large amounts of money through unscrupulous practices.

One of the most cited complaints among the Ojibwe at that time was a “dead and burnt wood” clause which allowed the lumber barons to purchase timber at a greatly reduced rate if it was in such condition. They would often start forest fires and then quickly harvest both semi-burnt and green wood and claim it all as “dead”, reaping massive profits at the expense of the Ojibwe.

In addition to practices such as these, timber was routinely appraised at a severely lower rate on the Reservations in Minnesota than it would have been elsewhere. Money received for the timber, which was intended to sustain the Ojibwe people was mishandled, misappropriated and frequently spent frivolously by Indian Agents on behalf of the Ojibwe. When the payments would come, they were notoriously late, much to the ire of the Pillagers and other bands at that time.

Mistreatment and injustices at the hands of U.S. Marshals and other agents also played a large role. Kickback schemes abounded between these federal agents and local hotel and railroad men, who were paid by the U.S. Government each time a witness or defendant was brought before the court in Duluth. Ojibwe were routinely rounded up and brought to Duluth on false charges to line the pockets of those involved in the scam.

Delayed payments and consistent arrests in weak, unsubstantiated bootlegging cases eventually led the leaders of the Pillager tribe to send a letter to the U.S. Government asking them to look into the on-going injustices the tribe was facing.

We, the undersigned chiefs and headmen of the Pillager band of Chippewa Indians of Minnesota, respectfully represent that our people are carrying a heavy burden, and in order that they may not be crushed by it, we humbly petition you to send a commission, to investigate the existing troubles here.

The Chippewa Indians of Minnesota have always been loyal to the United States and friendly to the whites, and they desire this friendship to be perpetual.

We now have only the pine lands of our reservations for our future subsistence and support, but the manner in which we are being defrauded out of these has alarmed us.

We trust that you will protect us when the truth reaches you.

The letter went unacknowledged by the U.S. Government, further perpetuating the poor relationship between the tribe and U.S. officials.

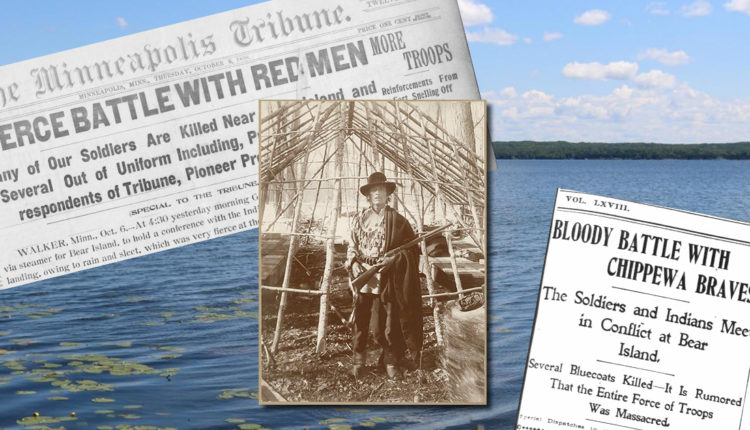

Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig (Hole-In-The-Day) was an elder Pillager man and one of the many Ojibwe who had first-hand experience of the downfalls within the U.S. justice system . In April 1898, Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig was arrested by a U.S. Marshal on bootlegging charges and brought to Duluth for court.

Once arraigned and let go due to insufficient evidence, Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig was left to make the 135 mile journey home on his own accord. Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig hitched rides on multiple trains, only making it so far in the journey before being repeatedly thrown off for not having a ticket. Leading him to eventually walk the last 40 miles home in his moccasins, wearing them down to his bare feet. It was at that moment he swore he would never allow himself to be arrested ever again, lest he may perish on his next forced journey home. He kept true to this word and never again sat before the U.S. Judicial system.

When Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig was called on to stand in Duluth as a witness for another bootlegging case a few months later, he ignored the U.S. Marshals warrant for his appearance. He was then detained along with Sha-Boon-Day-Shkong, another Pillager man when they went to collect their annuity payments in Onigum. Recognizing the stakes at hand at the possibility of another trip to Duluth, Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig called out for help. The other Ojibwe in Onigum, hearing the pleas of one of their elders, surrounded, and gently, yet forcefully secured his release.

The army officials who were in charge of the arrest of Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig that day, went forward to tell a tale of how they were surrounded by over 200 warriors and attacked, when in reality it was a small group of Pillager band members. Reportedly, less than 20 people, mostly women, aided in Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shigs escape.

Once the U.S. Army received word of Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shigs escape, they put out wanted notices for those reported to have been involved in his escape. To be certain those men were caught, they sent down an additional 77 soldiers from Fort Snelling.

The 80 soldiers began their quest that fateful morning and arrived on the shores of Sugar Point that afternoon. After failing to find Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig, the army set up base camp.

How the battle began has often been disputed throughout the years. The Pillager have held that the soldiers began firing on a canoe containing two women and a child as it rounded the corner of Sugar Point. The military claims that a rifle was accidentally discharged towards the Ojibwe side. Regardless, an intense firefight between the two sides erupted. The Pillager people went into that day not wanting battle but were prepared if it came.

The battle continued into the night and no harm came to any of the Ojibwe people outside of Indian Officer Gay-Gway-Day-Be-Tung (George Russell), who was allegedly shot by mistake, by a soldier who assumed he was fighting alongside the Pillagers. The 3rd U.S. Infantry saw six causalities and ten wounded that night.

On the morning of October 7, 1898, the soldiers retreated from Sugar Point, battered, hungry and cold. Once back to safety in Walker, the commanding officer, General Bacon, would be quoted in newspapers as saying that he “scattered” and “whipped the indians good”, a poor attempt at saving face.

Once word of the battle spread, hysteria ran rampant in the surrounding areas that an “Indian Uprising” was coming. Additional troops were sent to the area, and outcries to the US Government for assistance and protection were pouring in from the non-native people in Minnesota. Memories of Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn, just 22 years prior in 1876, led the newspapers of the day to run wild with unsubstantiated headlines.

The townspeople of Walker surrounded themselves with a 24-hour rotating shift of armed guards.. In Bemidji, all of the women were herded into a courthouse as 200 armed “militiamen” stood guard outside. It took a few weeks for the buzz to die down, though the relationships between the Ojibwe and their neighbors were never fully repaired.

With all of the nation’s attention turned towards Leech Lake, the U.S. Government was forced to hear the grievances put forth by the Ojibwe people. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, William A. Jones, was soon dispatched to the area. After an extensive number of meetings with the tribal elders, an agreement was reached. Several Pillagers turned themselves in for warrants related to Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig’s escape, although Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig himself upheld his pledge to never return to U.S. Court or jail. Most of those who turned themselves in served between two to six months, and everyone involved received a full pardon from President McKinley a short time after.

Further investigations revealed the damage that had been done to the Ojibwe at the hands of the logging companies, as well as during the first arrest of Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig and those who aided in his escape. Reforms in the management of timber on the Leech Lake Reservation eventually led to the establishment of the Chippewa National Forest.

None of the Pillager Ogichidaa who engaged in battle at Sugar Point ever were tried or received punishment for their involvement. Bug-O-Nay-Ge-Shig went on to live another 18 years in the area before passing peacefully. The U.S. Army never returned to the shores of Sugar Point on Leech Lake, the site of their final battle and defeat in the period now known as the “Indian Wars”.

Contributing Editor: Michael Chosa

Information and Figures corroborated by Author Greg Chester

References:

http://www.mngoodage.com/voices/mn-history/2017/09/the-battle-of-sugar-point/

www.mnhs.org/mnhistory

https://ss.sites.mtu.edu/mhugl/2017/10/21/battle-of-sugar-point-historical-marker/

https://www.leechlake.org/history/leech-lake-history.htm

Pillager letter provided by:

http://news.minnesota.publicradio.org/collections/special/1999/mncentury/9901/index.shtml

Audio

http://collections.mnhs.org/voicesofmn/index.php/10002857

http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/largerimage.php?irn=10278386&catirn=10372227&return=

http://news.minnesota.publicradio.org/collections/special/1999/mncentury/9901/index.shtml

https://beta.prx.org/stories/54246