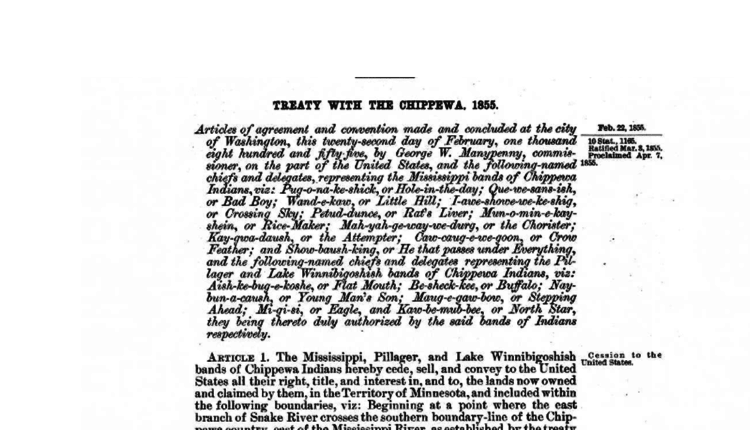

The Treaty of Washington, commonly referred to as the 1855 Treaty, was signed on this date in history between the United States government and representatives of the Pillager, Lake Winnibigoshish and Mississippi bands of Ojibwe.

This treaty established a reservation at Leech Lake for the Pillager & Lake Winnibigoshish bands and a reservation at Mille Lacs for the Mississippi bands. These reservations were established a full three years before Minnesota was admitted to the Union and recognized as a State in 1858.

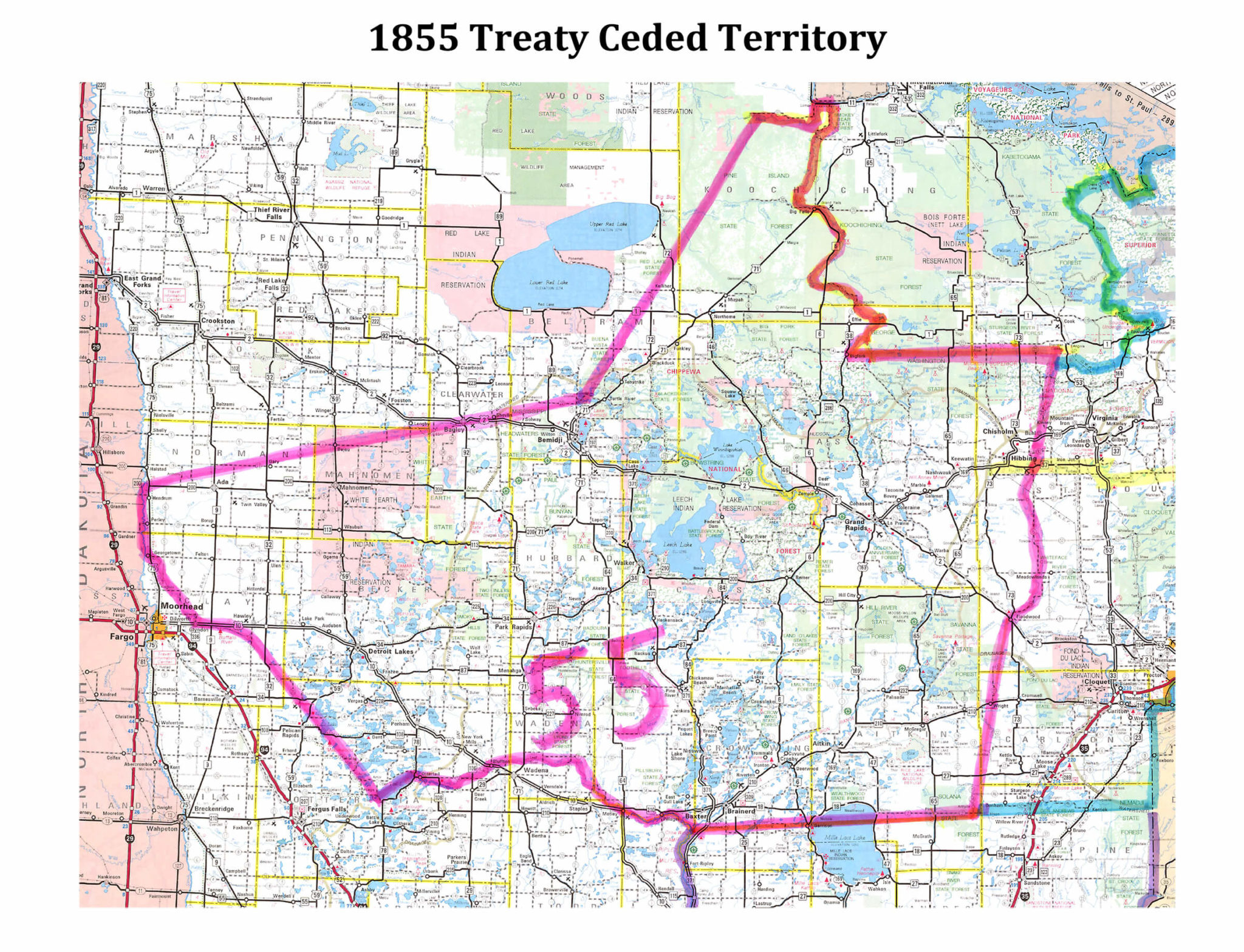

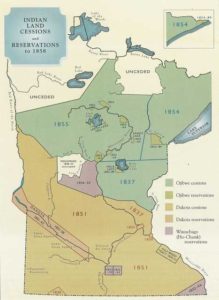

Much of the land in what would become Minnesota was acquired earlier through treaties with the Ojibwe in 1837 and 1854, and treaties with the Dakota in 1851 (see inset graphic). The United States wanted further access to lucrative logging and mining opportunities in north-central Minnesota, the 1855 treaty fulfilled their desires.

Hoping to avoid a similar situation to 1854 treaty negotiations, in which thousands of Ojibwe traveled to La Pointe to voice their concerns, the U.S. Government invited a small number of Ojibwe leaders to Washington D.C. The true purpose of their visit was kept secret from them until their arrival in the nation’s Capitol.

Negotiations were held for three days, from February 17 to February 20, 1855. In the end, a majority of the land in this territory was ceded to the United States with the exception of the newly established Leech Lake and Mille Lacs reservations.

Treaty Rights

While both the 1837 and 1854 included stipulations that the Ojibwe would retain their hunting and fishing rights in the ceded territory, the 1855 did not explicitly state this. This led to legal battles that are still being decided in court cases between band members and various county and state agencies.

At issue, are the usufructuary rights of Ojibwe band Members to hunt, fish and gather within the territories ceded in the 1855 treaty.

In a highly publicized decision, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed these rights for the Mille Lacs band in their 1999 decision.

“In 1837, the United States entered into a Treaty with several Bands of Chippewa Indians. Under terms of this Treaty, the Indians ceded land in present-day Wisconsin and Minnesota to the United States, and the United States guaranteed to the Indians certain hunting, fishing and gathering rights on the ceded land. We must decide whether the Chippewa Indians retain these usufructuary rights today. The State of Minnesota argues that the Indians lost these rights through an Executive Order in 1850, and 1855 Treaty, and the admission of Minnesota into the Union in 1858. After an examination of the historical record, we conclude that the Chippewa retain the usufructuary rights guaranteed to them under the 1837 Treaty”.

-Justice Sandra Day O‘Connor, U.S Supreme Court, 1999

Established in 2010, the 1855 Treaty Authority is leading the fight to have these rights legally recognized. The group includes members from the Ojibwe communities of East Lake, Leech Lake, Mille Lacs, Sandy Lake and White Earth. Twenty or so members meet monthly to work on strategies to force a legal decision on the matter and put the issue to rest once and for all.

Their most effective tactic to date, is public demonstrations of off-reservation hunting, fishing and gathering rights throughout the ceded territory. These demonstrations have included setting net and harvesting wild rice. The participating tribal members hope to receive citations from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources or county officials. The 1855 Treaty Authority then represents these Band members in state court, with the hope that a decision will be issued and elevated all the way to the United States Supreme Court in the same manner as the Mille Lacs Decision.

“The Anishinaabe-Ojibwe derive these rights from Gitchi Manidoo, the creator. These rights predate contact with the Europeans” says Bedonahkwaad, Dale Greene, 1855 Treaty Authority board member and enrolled member of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, “The concept of land ownership was such a foreign idea to the Indians at that time, How can you own the land? Will you pick it up and bring it with you wherever you go?”

He further states; “We maintained the right of occupancy, the right to exist off of our resources. The right to hunt, fish, gather and travel were unalienable to the Indians. The 1855 is important because it does not state that we are giving up any of these rights in the ceded territories. That’s the bottom line. We’ve already won, we are just waiting for the decision.”

Another crucial factor in the interpretation of the 1855 treaty is what is known as the reserved rights doctrine, which holds that any rights that are not specifically addressed in a treaty are reserved to the tribe. In other words, treaties outline the specific rights that the tribes gave up, not those that they retained.

The courts have consistently interpreted treaties in this fashion, beginning with United States v. Winans (1905), in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a treaty is “not a grant of rights to the Indians, but a grant of rights from them.” Any right not explicitly extinguished by a treaty or a federal statute is considered to be “reserved” to the tribe.

Read more:

Reserved Rights Doctrine -JRank Articles

Full Text of the 1855 Treaty

The Anishinabe Nation’s “Right to a Modest Living” by Prof. Peter Erlinder, Wm. Mitchell College of Law

Read More on the 1855 Treaty Rights Dispute

MPR Article (2/1/16) – “Original intent? History, language blur Minnesota Indian treaty disputes”

Audio version of “Original Intent…” MPR story (8min 13sec)

MPR Article (2/1/16) – “Tribal protesters plead not guilty to illegal fishing”

MPR Article (2/1/16) – “Explaining Minnesota’s 1837, 1854 and 1855 Ojibwe treaties”

MPR Article (1/8/16) – “Tribal protestors charged for gathering fish and wild rice”